Banisteriopsis cappi

Ayahuasca Vine

Ayahuasca is a traditional Amazonian brew made by combining the Banisteriopsis caapi vine with plants containing the psychedelic compound DMT. Used for centuries in Indigenous ceremonies, ayahuasca is revered for its powerful visions, emotional release, and spiritual insights, often accompanied by purging as part of its cleansing process. In modern contexts, it is sought both in ritual and retreat settings, as well as being studied for potential therapeutic applications.

Botanical Family

Malpighiaceae (Barbados Cherry Family); Pyra-midotorae, Banisteriae Tribe

Forms and Subspecies

Two varieties have been distinguished:

-

Banisteriopsis caapi var. caupari

-

Banisteriopsis caapi var. tukonaka

The first form has a knotty stem and is considered to be more potent; the second has a completely smooth stem.

The Andoques Indians distinguish among three forms of the vine, depending upon the types of effects each has upon the shamans: iñotaino (transformation into a jaguar), hapataino' (trans-formation into an anaconda), and kadanytain (transformation into a goshawk) (Schultes 1985, 62).

Download This Free PDF Infographic On Ayahuasca

History

The word ayahuasca is Quechuan and means "vine of the soul" or "vine of the spirits" (Bennett 1992. 492). The plant has apparently been used in South America for centuries or even millennia to manufacture psychoactive drinks (ayahuasca, natema, yahé, etc.). Richard Spruce (1817-1893) collected the first botanical samples of the vine between 1851 and 1854 (Schultes 1957, 1983). The original voucher specimens have even been tested for alkaloids (Schultes et al. 1969).

The German ethnographer Theodor Koch-Grünberg (1872-1924) was one of the first to observe and describe the manufacture of the capi drink from Banisteriopsis capi (1921, 190 ff.). The pharmacology was first elucidated in the mid-twentieth century.

Distribution

It is not certain where the plant originated, as it is now cultivated in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Brazil, that is, throughout the entire Amazon basin. Wild plants appear to be chiefly stands that have become wild (Gates 1982, 113).

Cultivation

The plant is cultivated almost exclusively through cuttings, as most cultivated plants are infertle (Bristol 1965, 207). A young shoot or the tip of a branch is allowed to stand in water until it forms roots, after which it is transplanted or simply placed into humus-rich, moist soil and watered profusely. The fast-growing plant thrives only 1a moist tropical climates and does not typically tolerate any frost.

Appearance

This giant vine forms very long and very woody stems that branch repeatedly. The large, green leaves are round-ovate in shape, pointed at the end (8 to 18 cm long, 3.5 to 8 cm in width), and opposite. The inflorescences grow from axillary panicles and have four umbels. The flowers are 12 to 14 mm in size and have five white or pale pink sepals. The plant flowers only rarely (Schultes 1957, 32); in the tropics, the flowering period is in January (although it can also occur between December and August), The winged fruits appear March and August (Ott 1996) and between resemble the fruits of the maple (Acer spp.). The plant is quite variable, which is why it has been described under several different names.

The vine is closely related to Banisteriopsis membranifolia and Banisteriopsis muricata and can easily be confused with these (Gates 1982, 113). It is also quite similar to Diplopterys cabrerana.

Psychoactive Material

-

Stems, fresh or dried (banisteriae lignum)

-

Bark, fresh or dried, of the trunk (banisteriae cortex)

-

Leaves, dried

Preparation and Dosage

In Amazonia, dried pieces of the bark and the leaves are smoked. The Witotos powder dried leaves so that they can smoke them as a hallucinogen (Schultes 1985).

The vine is rarely used alone to produce ayahuasca or yagé:

The Tukano prepare the yajé by dissolving it in cold water, not, as is done by other tribes to the south, by boiling. Short pieces of the liana are macerated in a wooden mortar, unmixed with the leaves or with other ingredients. Cold water is added, and the liquid is passed through a sieve and placed in a special ceramic vessel. This solution is prepared two or three hours before its proposed ceremonial use, and it is later drunk by the group from small cups. These drinking vessels hold 70 cubic cm and between drinks, six or seven in number, intervals of about an hour elapse. (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1970, 32).

In between they drink chicha, a slightly fermented beer, and smoke copious amounts of tobacco (Nicotiana rustica, Nicotiana tabacum).

The vine is usually prepared together with one or more additives so that it develops either psychedelic (using plants that contain DMT, primarily Psychotria viridis) or healing.

Small baskets made of strips of ayahuasca bark 4 to 6 mm in thickness (total dry weight = 13 to 14g) are now being produced in Ecuador; each basket corresponds to the dosage for one person. These little baskets are stuffed with leaves of Psychotria viridis (approximately 20g) and boiled to prepare a psychedelic drink.

Ritual Use

The Desana, a Colombian Tukano tribe, drink pure ayahuasca only on ritual occasions, although these do not have to be associated with any particular purpose, such as healing or divination. Only men may consume the drink, although the women are involved as dancers (i.e., as enter-tainment). The ritual begins with the recitation of creation myths and is accompanied by songs. It lasts for eight to ten hours. Very large amounts of chicha are also consumed while the ritual is in progress (Reichel-Dolmatoff 1970, 32).

Medicinal Use

In some areas of the Amazon, and among the followers of the Brazilian Umbanda cult, a tea made from the ayahuasca vine is drunk as a remedy for a wide variety of diseases and may also be used externally for massaging into the skin (Luis Eduardo Luna, pers. comm.).

Effects

-

Intense visual/auditory hallucinations

-

Purging (vomiting, diarrhea) seen as cleansing

-

Confronting trauma, deep emotional release

-

Spiritual insights, sense of guidance, interconnectedness

-

Dilated pupils

-

Increased body temperature, heart rate, and blood pressure

-

Sweating

-

Sleeplessness

-

Loss of appetite

-

Dry mouth

-

Tremors

Commercial Forms and Regulations

Pieces of the vine are only rarely offered in ethnobotanical specialty stores. There are no regulations concerning the plant. However, the preparation of Ayahuasca derived from the plant are generally illegal, but religious exemptions in Brazil, Peru, U.S. (e.g., Santo Daime, UDV churches).

Harm Reduction Tips

-

Medical screening before use (heart, mental health, medication risks)

-

Only use in safe, supportive, experienced ceremonial setting

-

Avoid mixing with other substances

Potential Risks

-

Risk of serotonin syndrome with SSRIs/antidepressants

-

Physical discomfort (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea)

-

Can trigger psychosis in predisposed individuals

Onset and Duration

Mechanisms of Action

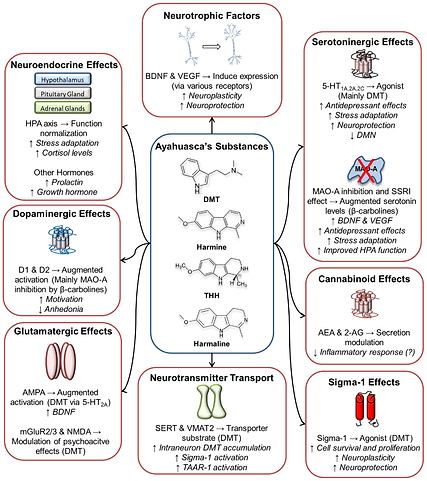

Pharmacology and Biochemistry

Mechanisms of action describe the specific biochemical and molecular interactions through which a substance or compound produces its pharmacological effects in a biological system.

Constituents

The entire plant contains alkaloids of the B-carboline type. The principal alkaloids are harmine, harmaline, and tetrahydroharmine.

Effects

The vine functions as a potent MAO inhibitor, whereby only the endogenous enzyme MAO-A is inhibited. As a result, both endogenous and externally introduced tryptamines, such as N,N-DMT, are not broken down and are thus able to pass across the blood-brain barrier.

When the vine is used alone, it produces mood-enhancing and sedative properties. In higher dosages, the harmine present in the plant (above 150 to 200 mg) can induce nausea, vomiting, and shivering (Brenneisen 1992, 460).

Rossi, G. N., Guerra, L. T. L., Baker, G. B., Dursun, S. M., Saiz, J. C. B., Hallak, J. E. C., & dos Santos, R. G. (2022). Molecular Pathways of the Therapeutic Effects of Ayahuasca, a Botanical Psychedelic and Potential Rapid-Acting Antidepressant. Biomolecules, 12(11), 1618. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom12111618

References

Brenneisen, Rudolf. 1992. Banisteriopsis. In Hagers Handbuch der pharmazeutischen Praxis, 5th ed.,

4:457-61. Berlin: Springer.

Elger, F, 1928. Über das Vorkommen von Harmin in einer südamerikanischen Liane (Yagé). Helvetica Chimica Acta 11:162-66.

Friedberg, C. 1965. Des Banisteriopsis utilisés comme drogue en Amerique du Sud. Journal d'Agriculture Tropicale et de Botanique Appliquée

12:1-139.

Gates, Brownwen, 1982. A monograph of Banisteriopsis and Diplopterys, Malpighiaceae. Flora Neotropica, no. 30, The New York Botanical Garden.

Hashimoto, Yohei, and Kazuko Kawanishi, 1973. New organic bases from Amazonian Banisteriopsis caapi. Phytochemistry 14:1633-35.

Hochstein, F. A., and A.M. Paradies, 1957. Alkaloids of Banisteria caapi and Prestonia amazonicum. Journal of the American Chemical Society 79:5735-36.

Mors, W. B., and P. Zaltzman. 1954. Sôbre o alcaloide de Banisteria caapi Spruce e do Cabi paraensis Ducke. Boletím do Instituto de Quimica Agricola 34:17-27.

Morton, Conrad V. 1931. Notes on yagé, a drug-plant of southeastern Colombia. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences 21:485-88.

Ott, Jonathan. 1996. Banisteriopsis caapi. Unpublished electronic file. Cited 1998.

Reichel-Dolmatoff, Gerardo. 1969. El contexto cultural de un alucinogeno aborigen: Banisteriopsis caapi. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 13 (51): 327-45.

Schultes, Richard Evans, 1985. De Plantis Toxicariis e Mundo Novo Tropicale: Commentationes XXXVI: A novel method of utilizing the hallucinogenic Banisteriopsis. Botanical Museum Leaflets 30 (3): 61-63.

Schultes, Richard Evans, et al. 1969. De Plantis Toxicariis e Mundo Novo Tropicale: Commentationes III: Phytochemical examination of Spruce's original collection of Banisteriopsis caapi. Botanical Museum Leaflets 22 (4): 121-32